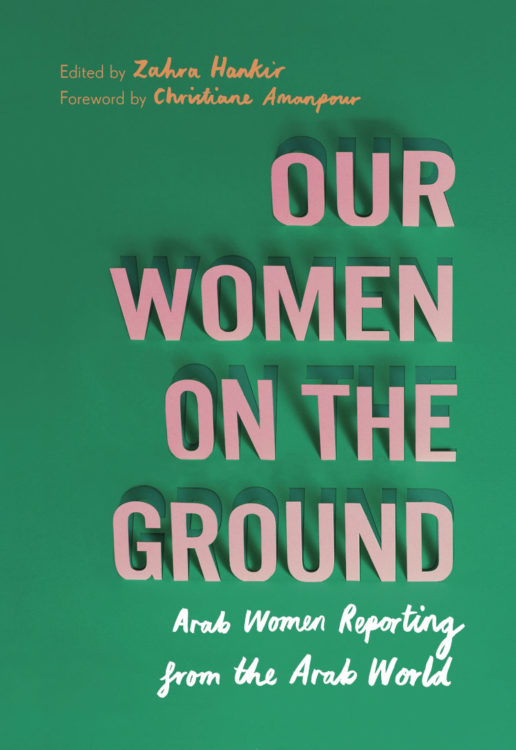

Zahra Hankir is a Lebanese-British journalist with degrees in politics and Middle Eastern studies. A guest of Writers’ Week 2020, her latest book, Our Women on the Ground, collates the writings of female Arab journalists. Her work has also appeared in Al Jazeera English, BBC News, Bloomberg Businessweek and many other respected platforms.

Whilst looking out of her London window at the snow, she took some time to answer the following questions for Glam Adelalide.

What first drove you to become a writer/journalist?

I was born in the United Kingdom during the Lebanese civil war to immigrant parents (we later returned to the country when the war subsided in the 90s). I identify as a liberal Muslim and consider myself a cross-cultural dual national. But my Arab identity is dominant and permeates all aspects of my being. It took time for me to come to that realisation, given the push and pull of straddling two worlds and speaking two languages as I came of age.

My Muslim upbringing in a Western cultural context at times enriched me as I grew up, while at others – particularly as a child, when I was bullied at school in England – it confused and unsettled me and was a source of contention. I was frequently made to feel like the “other”. My intense feelings towards the homeland I’d never lived in were somewhat poetic. My mother, who lived away from her family during the war in Lebanon, played romantic, nostalgic Lebanese music for me and my five siblings at home, particularly Fairouz. She cooked us Lebanese ambrosia and told us stories about our grandparents and her hometown. Those stories whisked us away into another land – far from Northern England – one that was filled with warmth and depth and treasures.

My career choice was profoundly tied to that upbringing and to my being Lebanese and Arab: news was a permanent fixture at home, as my parents often relied on journalists for updates on the situation in their hometown in South Lebanon, given that landlines were frequently down. Journalists were heroes to my mind – I grew up believing inherently in their power to tell stories that needed to be told, and to deepen our understanding of the world, particularly places mired by conflict.

As I grew up in Lebanon, my obsession with the Arab world, and the journalists telling its stories, deepened. I would say it culminated with this book project.

What, for you, are the hallmarks of great journalism?

Journalism that inspires change, whether in how one perceives a particular issue, or in how people or governments address it. Journalism that holds power in all its forms to account, and that humanises. Journalism that immerses the reader and that transports them into a different realm. Journalism that deepens our understanding of the world. Those are just some of the hallmarks of great journalism, to my mind.

In what ways are Arab women’s voices heard in their own countries? What can be done to improve the “gap in the narrative”?

It depends on the country and the context — some fare better than others when it comes to women’s rights and journalistic freedoms. That said, more can and must be done to protect women and to make space for and amplify their voices.

With respect to closing the gap: I would say the industries of publishing and journalism in the West in particular need to focus more on inclusivity and diversity, to incorporate the voices of those whose stories are already being told by Western foreign correspondents and writers into predominant narratives.

I hoped, through this book, to give Arab women journalists a global platform to share their experiences of reporting from and living in the region from which they hail — to help close the narrative gap, so to speak.

This platform is all-the-more important because the Arab world and its people are so often seen as homogenous when, as the essays in the book reflect, the geographic area is incredibly layered, and each country and conflict and experience carries unique and fascinating truths. The international media narrative on the Arab world has been dominated, for decades by Western correspondents who will sometimes cover the region for a year or two, go back to their home countries, then write about their experiences in memoirs or authoritative non-fiction books, or become talking heads. I figured: what about the fearless Arab women journalists? The women in this book demonstrate that without their voices and work, the stories of the region, with all of its nuances and intricacies and complexities, would remain partly told. My hope is that readers will come away from the book with a far deeper and more enriching understanding of the Arab world and broader Middle East, and a strong sense of the resilience of its women.

What threads did you see running through the essays you collected for the book?

The threads are laid out in the book and they became obvious to me after all of the essays came in: Remembrances, for the women who looked back on particular formative experiences, whether personal, professional or both; Crossfire, a double entendre for the women who have lived through or endured war and who have dual identities; Resilience, for the women who faced adversity and chose to focus their creative energies on rising above that adversity (this theme is applicable to all the writers, in fact, but heightened in these entries); Exile, for the women who were forced out of their homelands for their reporting or other reasons and who now live in foreign countries; and Transition, for those writing about societies or an industry in transition. One thread which ran throughout all of these sections was also Guilt: guilt that these women were perhaps not doing enough justice to the story, or guilt that they were experiencing some sort of privilege when comparing their own circumstances to that of those who are worse off.

Are there particular ways in which Australians, and in particular Australian women, can support our Arab sisters in their struggle for a voice?

Thank you so much for asking this question. By reading and helping promote our work! I tend to say we very much have voices — there is no struggle in that respect — but we still have a long way to go in terms of getting our voices out there, particularly in established, mainstream literary spaces. I’d say bringing attention to the nuance of the region and its people might help increase understanding.

Other than speaking at Writers Week, are there any other activities you have planned while you are in Adelaide?

I’m hoping to meet writers from all over the world whose work I’ve read, and I’ll also be spending some quality time with Azadeh Moaveni, author of Guest House for Young Widows. We’re close friends — our books brought us together — and I can’t wait to explore Adelaide with her. We’re hoping to engage in a couple of cultural activities, to sample some local cuisine, and to get some much-needed sun, time-permitting. It’s presently snowing in London! I’m also going to try to sneak in the Botanic Gardens and Waterfall Gully.

Interviewed by Tracey Korsten

Twitter: @TraceyKorsten

Zahra Hankir appeared at Writers’ Week 2020 in Women in War with Sophie McNeill on 2 March and The Challenge of Change: Women’s Lives in the Middle East with Azadeh Moaveni and Jokha Alharthi on 4 March.